Preserving Columbia’s

oldest Post-Reconstruction

African American burial ground

Safeguarding Over 100 Years Of History

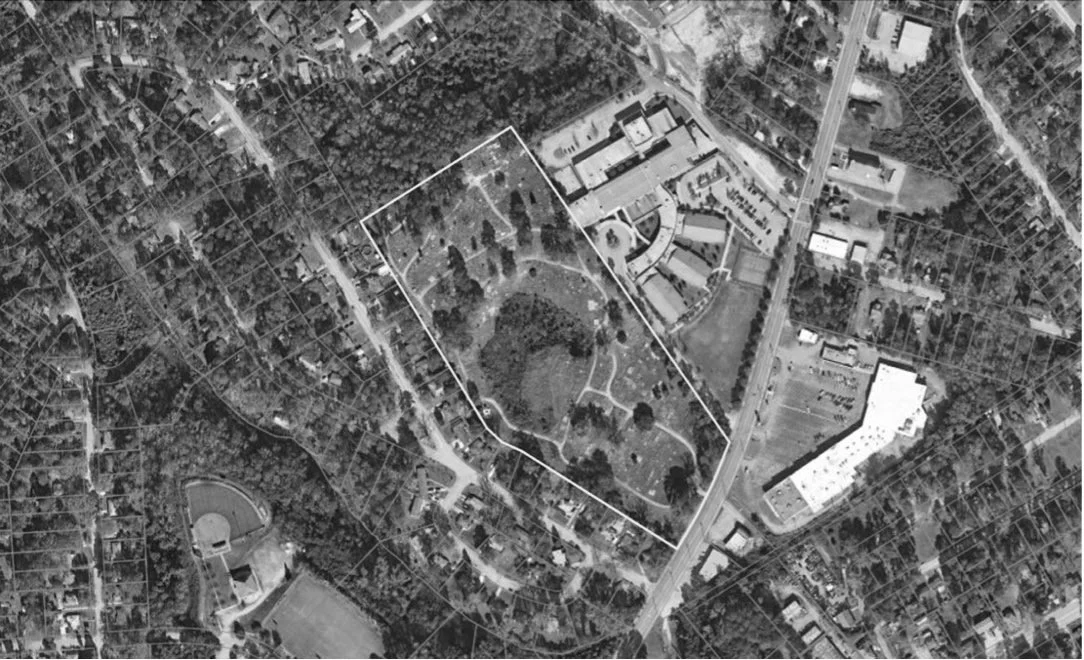

The Palmetto Cemetery is a historically African American vernacular cemetery in Columbia, South Carolina, established by funeral home director Willis Craig Johnson of the formerly prestigious Johnson’s Funeral Home in 1920. As one of the only burial grounds reserved as the final resting place for African Americans in South Carolina’s capital city, the cemetery reflects the political turmoil of the period post-Reconstruction and the growing sense of community harnessed among free African Americans in society seeking to dignify and honor the lives of deceased community members during the advent of restrictive Jim Crow laws that enforced racial segregation and other such circumstances impacting African American life in the Deep South.

The burial ground’s distinctive, vast, and unplanned arrangement, assortment of markers, and landscape illustrate the funerary and burial customs of Columbia’s black community during the decline of the rural cemetery movement.

Today, the cemetery is privately owned by the Palmetto Cemetery Association, a 501(c)3 nonprofit with a mission to engage descendants of the interred and the wider community in the restoration, protection, care, and public awareness of the cultural heritage site.

Continuing the Legacies of Our Ancestors

“Palmetto Cemetery is more than just a cemetery, its history. It’s the history of the African American community in Columbia. If you’ve ever lived in this city, chances are you have a family member buried there. We have an obligation as human beings to preserve the resting places of our loved ones and continue their legacies.”

Vanessa Briggs

President, Palmetto Cemetery Association

Honoring Columbia’s Black Luminaries from 1920-1992

Palmetto Cemetery is the final resting place for many of the city and state’s most significant Black luminaries from 1920 to 1992.

-

On May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka struck down racial segregation in schools, effectively overturning the “separate but equal doctrine” codified in Plessy v. Ferguson nearly 60 years before. For Modjeska Monteith Simkins, who co-authored the petition that became Briggs v. Elliott, one of the five cases that comprised the Brown decision, the Supreme Court’s ruling was far from either the beginning or the end of a lifetime spent fighting for human rights. Over the course of her 92 years, she displayed a courage and perseverance that many argue was unmatched.

-

Matilda Arabella Evans, who graduated from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) in 1897, was the first African American woman licensed to practice medicine in South Carolina. Evans's survey of black school children's health in Columbia, South Carolina, served as the basis for a permanent examination program within the South Carolina public school system. She also founded the Columbia Clinic Association, which provided health services and health education to families. She extended the program when she established the Negro Health Association of South Carolina, to educate families throughout the state on proper health care procedures.

Matilda Arabella Evans was born in 1872 to Anderson and Harriet Evans of Aiken, South Carolina, where she attended the Schofield Industrial School. Encouraged by Martha Schofield, the school's founder, Evans enrolled in Oberlin College in Ohio, attended on scholarship for almost four years, and left before graduating, in 1891, to pursue a medical career.

After teaching at the Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia and at the Schofield School, Evans enrolled at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1893. She received her M.D. in 1897 and returned to Columbia, South Carolina, where she established a successful practice. As the first African American woman licensed to practice in South Carolina, she treated both white and black patients, and was in great demand. She practiced obstetrics, gynecology, and surgery, and cared for patients in her own home until she established the Taylor Lane Hospital (the first black hospital in the city of Columbia) in 1901. By 1907 Dr. Evans was able to write to Alfred Jones, Bursar at Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania, "I have done well, and have a very large practice among all classes of people... I have had unlimited success... Since I have returned to my native state, others have been inspired and have gone to our beloved college to take degrees." She was writing on behalf of a promising young African American woman who wanted to attend WMCP but was in need of scholarship assistance.

Evans ran her own farm and founded a weekly newspaper, The Negro Health Journal of South Carolina, and offered a program of recreational activities for underprivileged boys. Dr. Evans was elected president of the Palmetto State Medical Society and vice president of the National Medical Association, and in World War I was appointed to the Volunteer Medical Service Corps.

-

Celia Emma Dial was born enslaved in Columbia just one city block west of the Antebellum era University of South Carolina, but she has become known as one of the city’s most celebrated educators. Emancipated at age six, she attended three private schools and O. O. Howard School, the first public high school for Black students in the state. Dial was one of a few women graduates to earn a teaching credential from the State Normal School hosted at the University of South Carolina in 1877. She began a teaching career at age 20 in Columbia’s Black public schools. Celia Dial Saxon’s teaching appointments mostly included secondary schools such as the Howard School and Booker T. Washington High School. Her dedication in the classroom was so great that she only missed three days of work in a 57-year teaching career. In addition to her career in primary and secondary education, she taught history and geography to undergraduates, graduate students, educators and others at summer institutes at Benedict College and South Carolina State A&M College (now South Carolina State University). In 1926, she was conferred an honorary master’s degree from South Carolina State A&M College.

As a member of the State Federation of Negro Women’s Clubs, Saxon was one of the founders of the Fairwold Industrial School for Negro Girls in Columbia, S.C., the Wilkinson Orphanage for Negro Children in Cayce, S.C., and the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the YMCA at the corner of Hampton and Park Streets. The location became home to the first public library available to Black patrons in the city; though in a new location, the Phyllis Wheatley Branch of the Richland Library still stands. She also served as the longtime treasurer of the Palmetto State Teachers Association. She died in January 1935.

At least four locations within the Columbia area have been named in honor of Saxon, including the Celia Dial Saxon Negro Elementary School in Columbia, S.C., which was open from the early 1930s to 1955 on Blossom Street. The Columbia Housing Authority opened Saxon Homes, a multi-million dollar 1,400-unit segregated housing project in downtown Columbia in 1954. Saxon Homes was razed in 2000, and a brand-new, mixed-income neighborhood – the Celia Dial Saxon neighborhood – began construction and home sales in 2003; the new neighborhood is home to the Celia Saxon Health Center, a Prisma Health facility.

-

Nathanial Frederick was born on November 18, 1877, in Orangeburg County, the son of Benjamin Glenn Frederick and Henrietta Baxter. He earned a B.A. from Claflin College in 1889 and a degree in history and Latin from the University of Wisconsin in 1901. He married Corrine Carroll on September 14, 1904. They had four children. Frederick served as principal of Columbia’s Howard School from 1902 until 1918. During this period he also read law. Admitted to the South Carolina Bar in 1913, he opened a law office in Columbia the following year.

Despite the racial barriers that hampered African Americans in the early twentieth century, Frederick became a successful lawyer. Before his death in 1938, he appeared before the South Carolina Supreme Court thirty-three times, more than any African American lawyer up to that time. He won twelve appeals and three of his four criminal cases that appeared before the court. Two of his legal victories drew national attention. In the 1926 case of State v. Lowman, Frederick represented three members of the Lowman family, African Americans who had been convicted of murdering the sheriff of Aiken County. Taking the case on appeal, Frederick won a unanimous order for a new trial. At the retrial, Frederick obtained a directed verdict of acquittal of Demond Lowman. The expectation was that a similar result would be obtained the next day for Bertha Lowman and her cousin Clarence. However, Demond was immediately rearrested. On the evening of October 8, 1926, all three Lowmans were dragged from jail and lynched. Despite editorial campaigns and three grand jury investigations, no one was ever brought to trial for the lynching.

The 1929 case of Ex parte Bess had a less tragic ending. Ben Bess was a black man who had been convicted of sexually assaulting a white woman. After Bess had served thirteen years of a thirty-year sentence, his alleged victim recanted her testimony. Using the recantation, Frederick obtained a pardon from Governor John G. Richards. After threats of prosecution for perjury, however, the alleged victim withdrew her recantation, whereupon the governor tried to revoke the pardon. Frederick immediately challenged the governor. The state supreme court sat en banc, with all the state circuit court judges, and in a ten-to-eight decision ruled that the governor could not revoke his pardon. Fearing a repeat of the Lowman lynching, Frederick immediately moved Bess out of state.

Frederick was active in other areas of South Carolina’s African American community. He was a crusading newspaperman, serving as editor of the Southern Indicator and the Palmetto Leader. He helped organize the Victory Savings Bank, a black-owned financial institution in Columbia. He was active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and served on its national legal committee. An ardent Republican, Frederick was a delegate to the party’s national conventions in 1924, 1928, and 1932. He died in Columbia on September 7, 1938, nearly destitute and was buried in Palmetto Cemetery, Columbia.

-

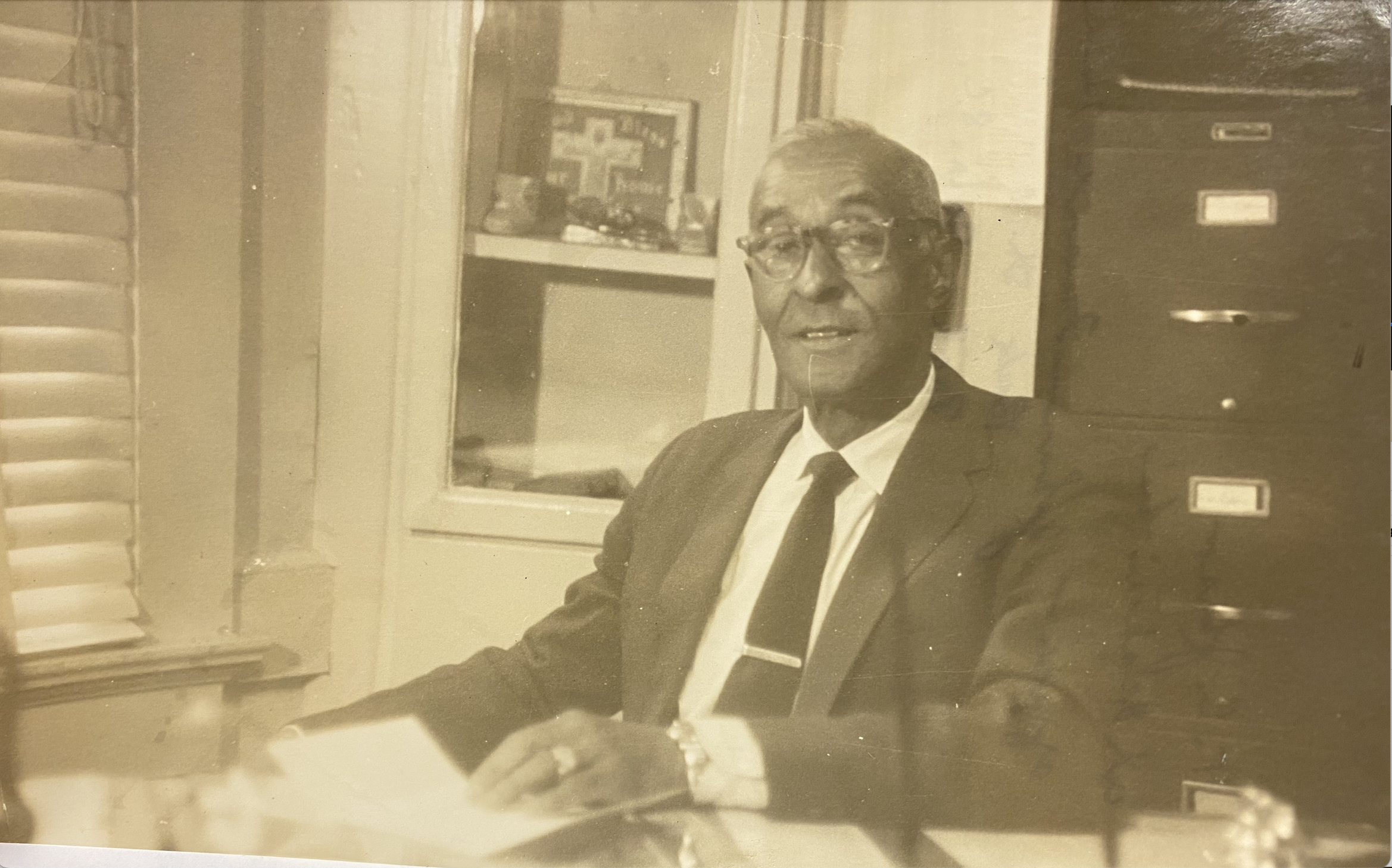

Edmund Perry Palmer, Jr. (E. Perry) was literally born in the funeral home in 1935, began working with his parents at the funeral home as a young boy and knew that it was his lifelong ambition. In 1957, after graduating from Mather Academy, Camden; North Carolina A & T College, Greensboro; and the American Academy of Funeral Service, New York, E. Perry Palmer became a full-time member of the firm in Sumter. In 1970, he and his wife, Grace Brooks Palmer moved to Columbia and purchased the former Johnson Funeral Home. In 1982, after a fire destroyed the facility, the business was renamed Palmer Memorial Chapel to reflect the family name. E. Perry Palmer was the recipient of numerous awards and citations including the Humanitarian of the Year Award.

It Takes A Village to Preserve Our Heritage

Make a contribution, volunteer, or share memories about your ancestors to help us preserve and sustain the legacy of one of Columbia’s oldest historically African American cemeteries. Gifts of all sizes help us to ensure our sacred burial ground is never forgotten.

Contact the

Palmetto Cemetery Association

Location

5105 Fairfield Road

Columbia, SC 29203Mailing Address

The Palmetto Cemetery Association

Post Office Box 2223

Columbia, SC 29202

Tel: (803) 360-4946